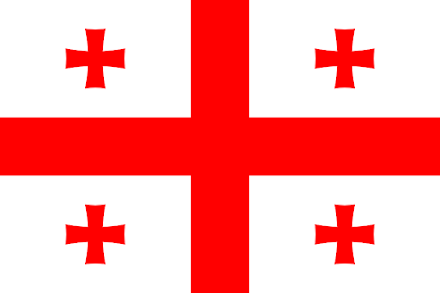

A study of the failures of Russian foreign policy in Georgia

A study of the failures of Russian foreign policy in Georgia

It is easy to divide Georgia since

independence into two periods, one before the Rose Revolution in late 2003 and

one after. The Russian view of the Rose Revolution is as a pro-western foreign-planned

coup.[2] This

misses a very important point, which is that Georgia was not particularly pro-Russian

on the eve of the revolution in 2003, and therefore Russian foreign policy in

Georgia must have failed without any alleged western coup.

Directly after the fall of the Soviet Union

the former Soviet republics formed the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States),

which all of the former Soviet republics have been members of or deeply

involved with, with the exception of the three Baltic states. The role and

purpose of the CIS is to facilitate trade and political cooperation between member

states. With Russia as the largest member in area, population, and economy and

its great interests in seeing the old Soviet space stand united, it is easy to see

the CIS as a Russian tool to maintain influence through economic cooperation. In

that regard the CIS has largely failed, however, with mostly ceremonial and

nominal cooperation agreements.[3] As

Georgia never joined the later organizations of the CSTO (Collective Security

Treaty Organization) or the EEU (Eurasian Economic Union) this CIS was the only

official link Georgia had to the Russian sphere. Georgia did not, however, join

the CIS initially.

The poor post-Soviet Russia failed to

influence Georgia through trade, and instead exploited the opportunities

presented by Georgia’s internal armed struggles. In the years 1991-1993, three

wars were ongoing almost simultaneously in Georgia, all of them with a degree

of Russian involvement. Two of these wars were the independence struggles of

the Abkhaz and Ossetian peoples against the Georgian government. Ossetian

rebels fought the newly established national guard in a slow struggle to

control the South-Ossetian region. There was significant support for the South-Ossetian

rebels in the Russian parliament, and Russian troops and helicopters fired on

Georgian forces on multiple occasions.[4]

Less than two months after the end of the

war in South-Ossetia, hostilities broke out in Abkhazia. The war in Abkhazia

was a similar story to that in South-Ossetia, but with a larger separatist

population and a more prepared Georgian army. The Russian parliament condemned

Abkhazia, and as with South-Ossetia the Russian army sporadically clashed with

Georgian forces. A critical difference between Abkhazia and South-Ossetia was

that the Abkhaz people may not have been the majority of the population in

Abkhazia prior to the war. As the war ended in a Georgian defeat, 250 000

Georgians, nearly half of the territory’s population, fled for Georgia.[5] The

two separatist wars left hundreds of thousands of Georgians homeless, and internally

displaced people are still more than 8% of the country’s population.[6]

While parts of the Georgian army fought in

South-Ossetia, the Georgian military overthrew the government of the

democratically elected president Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Civilian power was then

handed over by the military to the former leader of Soviet Georgia and last

foreign minister of the USSR, Eduard Shevardnadze. Though the Russian

government supported Shevardnadze, the coup was made by the army leadership

without any known Russian influence. When Gamsakhurdia returned to take power

by staging a revolt in western Georgia, approximately two thousand Russian

soldiers intervened with the stated objective of “protecting the railroads” and

defeated Gamsakhurdia.[7]

The Russian military ended up supporting

both the separatist republics and the military council in Georgia that fought

them. This was the result of a strategic and political disagreement between communist

and nationalist Russian parliamentarians on one side, and president Boris

Yeltsin with his liberal and capitalist reformers on the other. As the Abkhaz

war was ending, president Boris Yeltsin committed a coup against his own

parliament after a tense political standoff. The Russian parliament had

attempted to impeach Yeltsin, and their preferred president was the vice

president Alexander Rutskoy, who had threatened direct intervention in South

Ossetia.[4] While the constitutional crisis in 1993 was caused by a

long-standing conflict between Yeltsin and remnants of Soviet power, among

other things it ended the strategic ambiguity surrounding Russian policy in

Georgia.

A possible answer to the opening question

emerges here: the Russian methods of exerting influence are often internally

contradictory, leaving neither side in the conflict they partake in pleased. Abkhazia,

while having received support from Russia during the war, suffered under an

economic blockade imposed by the CIS, Russia included, in the years following.[8] The

Russian forces and weapons in Abkhazia soured relations with Georgia, and the

blockade that attempted to smooth over relations with Georgia soured relations

with Abkhazia.

Despite owing his power in part to Russian

military force, Shevardnadze was by no means a puppet of Yeltsin’s Russia. This

was made abundantly clear with Shevardnadze’s preference for defense

cooperation with NATO rather than Russia. While Georgia signed on to the

Collective Security Treaty (CST, the predecessor to the CSTO) in 1994, the

country did not re-sign the treaty when it expired in 1999. Indeed, Georgia’s

cooperation with NATO also had its humble beginnings in 1994, when Georgia

joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace program.[9]

Two failures of Russian policy helped

influence Georgia’s and Shevardnadze’s decision to begin pivoting away from

Russian defense cooperation and towards the west and NATO. The first reason is

that Russia had proved in the case of the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan,

both signatories to the CST, that Russia is not capable of defending its

members nor capable of mediating in a war between its own allies.[10] The

second reason is that Shevardnadze appears to have believed that Russia was the

most credible foreign threat against Georgia.[11]

While Shevardnadze’s Georgia was abandoning

Russian military cooperation in the late 1990s, Russia was the one abandoning

economic partnership with Georgia. After the end of the Abkhaz war and the

constitutional crisis in Russia, Shevardnadze joined the CIS, something president

Gamsakhurdia previously had avoided. This high point in post-Soviet

Russo-Georgian relations was seemingly not meant to last with Yeltsin’s

presidency nearing its end, and the old KGB agent and war hawk Vladimir Putin

silently chosen for the presidency in late 1999. In the year 2000 Russia

imposed a visa regime on Georgia, the first restriction of free travel within

the CIS in its history.[12]

When the Rose Revolution happened in 2003

it was not primarily over concerns about Russian influence. Eduard Shevardnadze

had, with a nine-year break in the middle, ruled Georgia since 1972. His

attempts to silence opposition, silence independent media combined with his

election rigging and general apathy towards corruption made the people choose

to act.[13] The

revolution was followed by the election of Mikheil Saakashvili with broad

popular support, and his further push for western integration and NATO

membership.

Russian president Vladimir Putin was not

pleased with the potential expansion of NATO into the Caucasus. At the Munich

security conference in 2007 he spoke out against NATO expansion in eastern

Europe, claiming it was a breach of oral assurances given to Gorbachev shortly

before the end of the Warsaw Pact that NATO would not expand into eastern

Europe.[14] In

March of 2008 Russia lifted the CIS sanctions on the breakaway republics of Abkhazia

and South-Ossetia, and almost immediately after Russian investment and aid

flooded into the republics.[15] In

other words, Putin at last chose the separatists over Georgia.

In April 2008 Georgia attended its first

NATO summit in Bucharest, where the organization pledged to accept Georgian

membership, should the country fulfill the necessary criteria.[9] This

both confirmed Russian fears and seemed to bolster Georgia. Russia was massing

troops around Georgia and in both of the separatist republics, while Georgia

assembled their forces in Gori, close to the South-Ossetian capital of

Tskhinvali.

The Russo-Georgian war began on the 7th

of August, and both sides maintain that the other fired first. The first

maneuver of the war was a Georgian offensive against the South-Ossetian capital

Tskhinvali. A Russian counteroffensive ended the war before the end of the 12th.

The motives of the Georgian offensive are in some dispute, with Georgian claims

of self-defense brought into question by the amount of preparation in Gori.[16]

After the ceasefire agreement of August 12th,

the Russian army did not halt within the borders of the separatist republics,

and instead occupied parts of Georgia proper. Russian forces occupied the

cities of Gori, Poti, Senaki, and Zugdidi, and blocked Georgia’s main east to

west highway and main port.[17] The

Russian army did not move to take Tbilisi, and no intention was shown of

overthrowing the Georgian government or permanently occupying the territories. The

most direct consequence of the occupation was harming the Georgian economy,

with the war potentially costing Georgia 2 billion euros in the long term.[18]

Shortly after the end of the war, Russia

formally recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South-Ossetia, to much

jubilation in the breakaway republics and in spite of much condemnation by the

west.[19] Russian

forces remain in the separatist republics at the time of writing, and they are

considered to be occupied territories of Russia. Georgia’s political response

to the war was not to end or reconsider their NATO membership, but instead to

leave the CIS.[20]

It may be impossible to track down a single

unified reason for why Russian policy decisions failed to keep Georgia in the

Russian sphere, but a part of the explanation is found in the Russian ambiguity

on whether to support Georgia or the separatists. Russian support of the two separatist

republics made Russia unpopular with Georgians, a sentiment that never fully

disappeared even when Yeltsin chose Georgia. With Putin came a return to the

separatist supporters in Russia. After the war Russia had won control over the

two breakaway republics, but the war also made it inconceivable for an openly pro-Russian

party to ever win a Georgian election again.[21]

For a moment there was a vaguely

pro-Russian government in Georgia, when Shevardnadze in 1993 and 1994 signed himself

and Georgia into both political, economic and defense cooperation with Russia. If

Russian leadership had faith that Shevardnadze would stick by them simply

because of their support of his coup, they were mistaken, but it was still not

impossible to rule Georgia with a vaguely pro-Russian stance in the 90s.

The problem with sticking with Russia for a

country like Georgia is that Russia does not have much to offer as an ally. In

the year 2000 the EU had an economy nearly 30 times the size of Russia, making

the offer to partake in a European market more tempting than to keep Russia as

Georgia’s largest trading partner. If Russia only threatened countries leaving

its sphere of influence it might serve as an incentive to stick with them, but

the Russo-Belarusian “Milk war” (a trade war caused by Belarus’ refusal to

recognize Abkhazia and South-Ossetia) proves that Russia does not shy away from

pressuring and threatening even their closest allies.[22]

The Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine in 2013-2014

was caused by outrage that Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych chose a

Russian trade deal over a European one, proving both that Russia does not

accept countries deviating from its trade sphere and that ordinary people will

choose to live in a country with better trade relations and a better economy, including

if it means moving away from Russia.[23] For

Georgia it simply did not make sense to keep Russia as their principal partner

and ally. As the EU is becoming an increasingly more important trade partner

for Central Asia, where over half of Putin’s formal allies remain, this may be an

issue that Russia will have to face again.[24]

Sources:

[1] The Russian foreign

policy term for the nations formerly in the USSR

[3] https://carnegieendowment.org/2017/06/30/whose-rules-whose-sphere-russian-governance-and-influence-in-post-soviet-states-pub-71403

[16] https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/did-saakashvili-lie-the-west-begins-to-doubt-georgian-leader-a-578273.html

[18] https://wiiw.ac.at/press-release-economic-consequences-of-the-georgian-russian-conflict-english-pnd-19.pdf

Comments

Post a Comment